In the late 19th century, criticism of the materialism of industrialized society began to emerge. Many sought a new, nature-oriented way of life. Friedrich Nietzsche’s writings were avidly read, and Richard Wagner’s opera Parsifal was interpreted as a pacifist manifesto. The “painter prince” Hans Makart depicted scenes from the Ring des Nibelungen. Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach—a devoted admirer of Wagner, artist-prophet, and nudist—founded a rural commune near Vienna in 1897. The Vienna Secessionists embraced Wagner’s ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art).

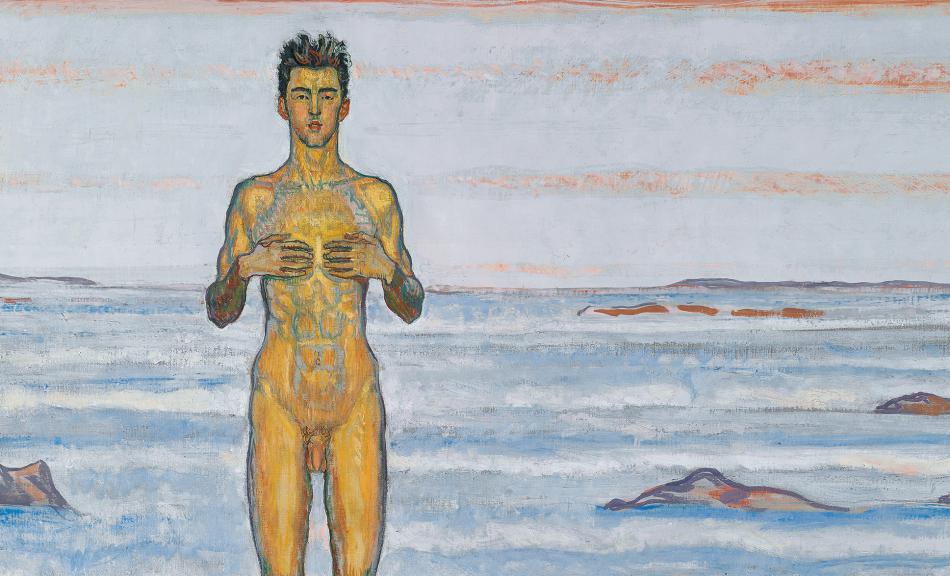

Vegetarian salons frequented by Vienna’s intellectuals became a conduit for modern theosophy, influenced by Eastern thought. Marie Lang, a women’s rights activist and advocate of the social reformist settlement movement, also hailed from a theosophical milieu; her son, Erwin Lang, captured the expressive dance of the Wiesenthal sisters in his paintings. Spiritualism offered further niches for women: Gertrude Honzatko-Mediz created mediumistic drawings. In neighboring countries, trance states were documented by established painters such as Albert von Keller and Gabriel von Max. The writer August Strindberg, deeply inclined toward esotericism, painted dark landscape visions. His friend Edvard Munch, along with the belief in life-giving invisible rays, inspired new artistic impulses. Artists such as Richard Gerstl, Arnold Schönberg, Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, and Max Oppenheimer saw their models as auratic presences. Modern psychology fused with dreamlike revelations, and the emergence of abstract painting would scarcely have been conceivable without the influence of occult literature.

For the first time in Vienna, a major exhibition examines the search for the “New Human” without ignoring the darker aspects of magical thinking. In this sense, the project Hidden Modernism also contributes to a critique of the present.

GET YOUR TICKETS

DIGITAL EXHIBITION

Media partners of the exhibition:

|

|

|

With kind support by:

|

Share and follow