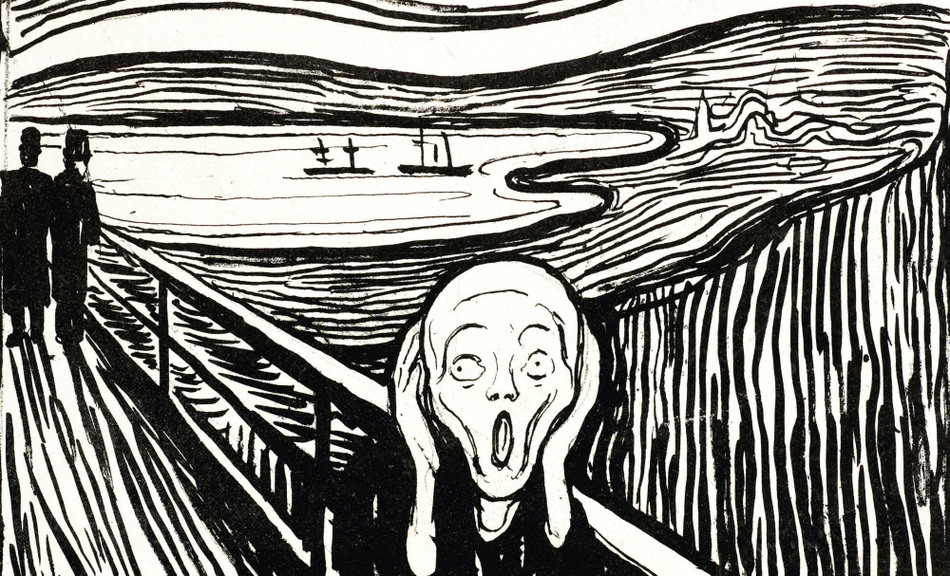

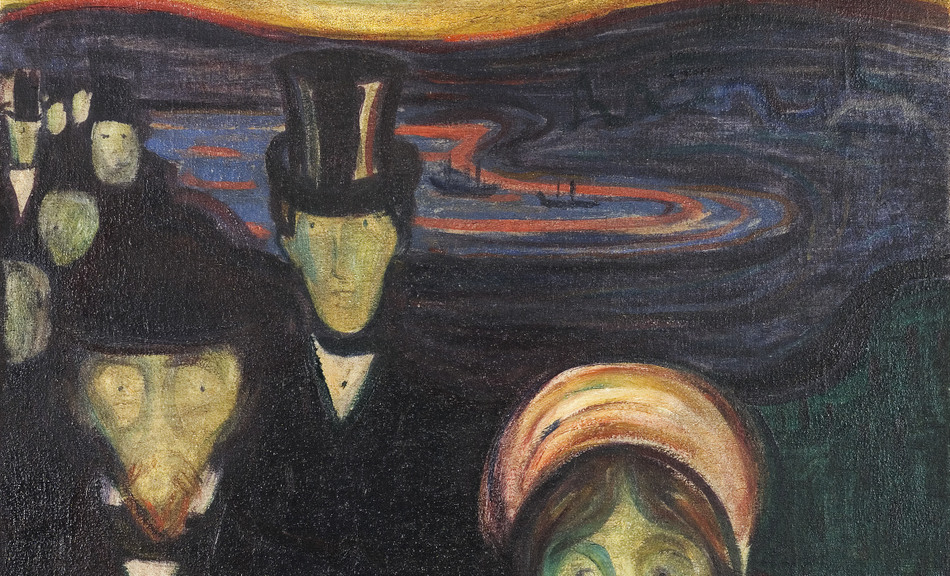

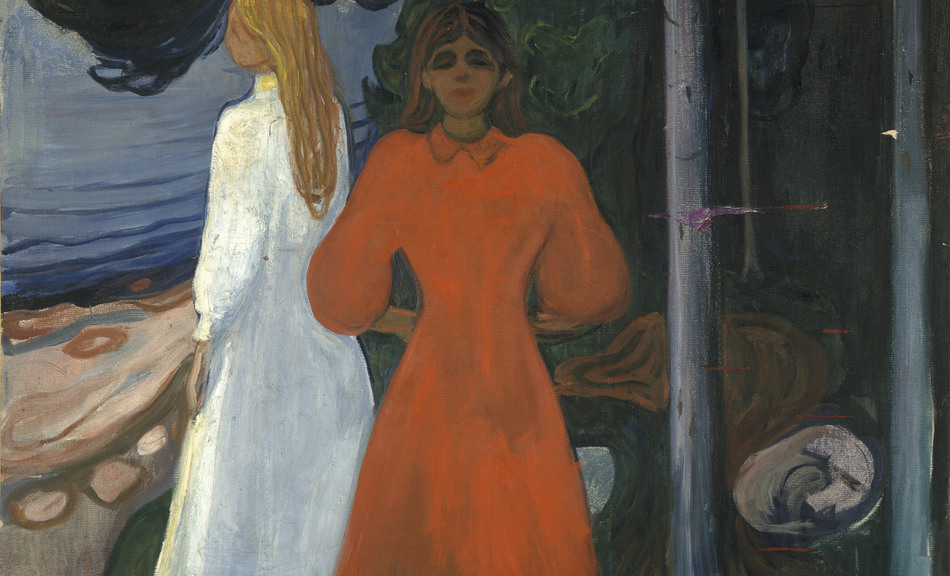

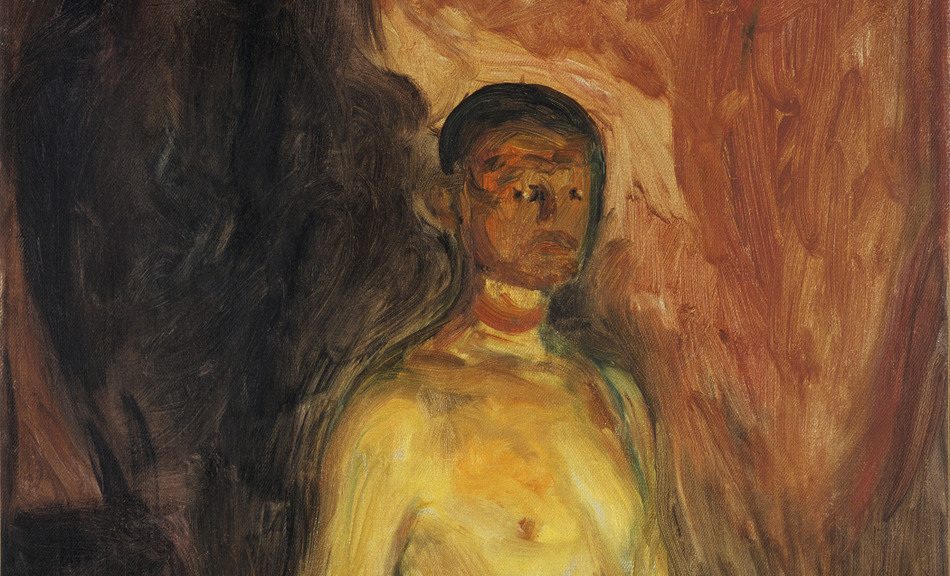

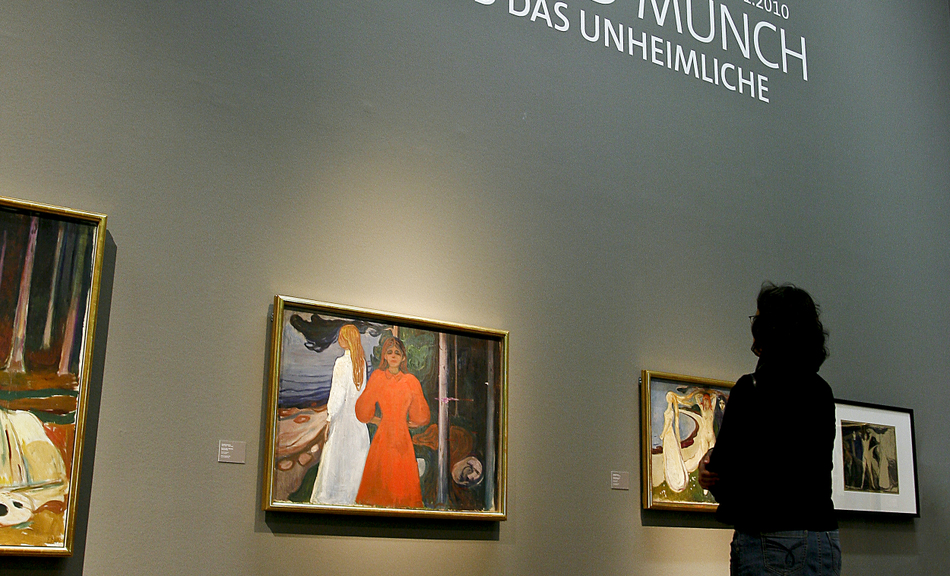

Edvard Munch, one of the most important European artists, stands at the center of the main autumn exhibition of the Leopold Museum. The themes of love, fear and death dominate Munch’s oeuvre. The symbol-laden atmosphere lends many of his works an air of uncanniness. The artist’s emotional states and inner conflict manifest themselves in drastic pictorial inventions, such as in the works Angst and The Scream. Tragedy in a sexual relationship becomes clear in the painting Vampire, in which the woman with the snake-like red hair sucks out the blood of her “male victim.”

The exhibition Edvard Munch and the Uncanny contains works ranging from the late 18th century (Piranesi, Goya’s “Caprichos”) up to the early 20th century. In his 1919 essay on “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud was then to examine the artistic and psychological concepts that are associated with this term.

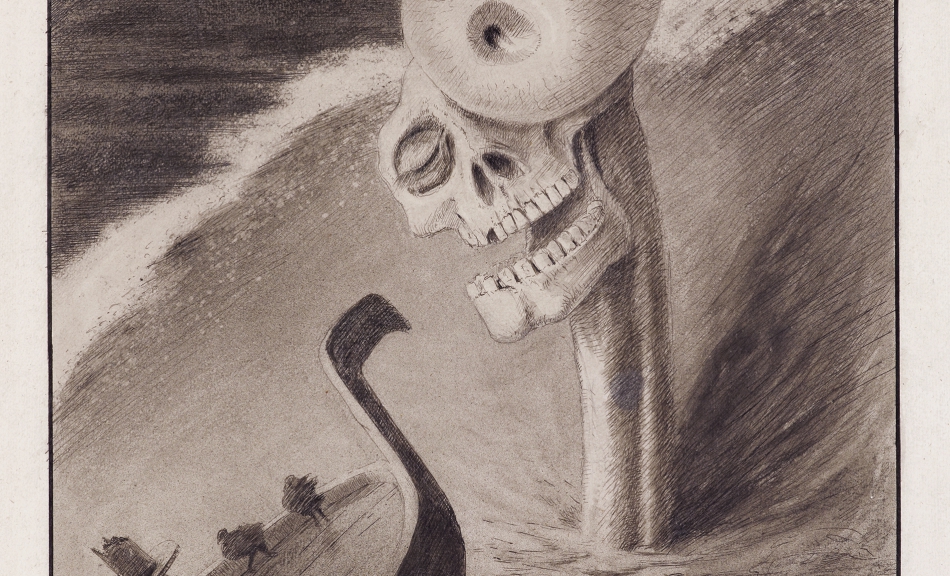

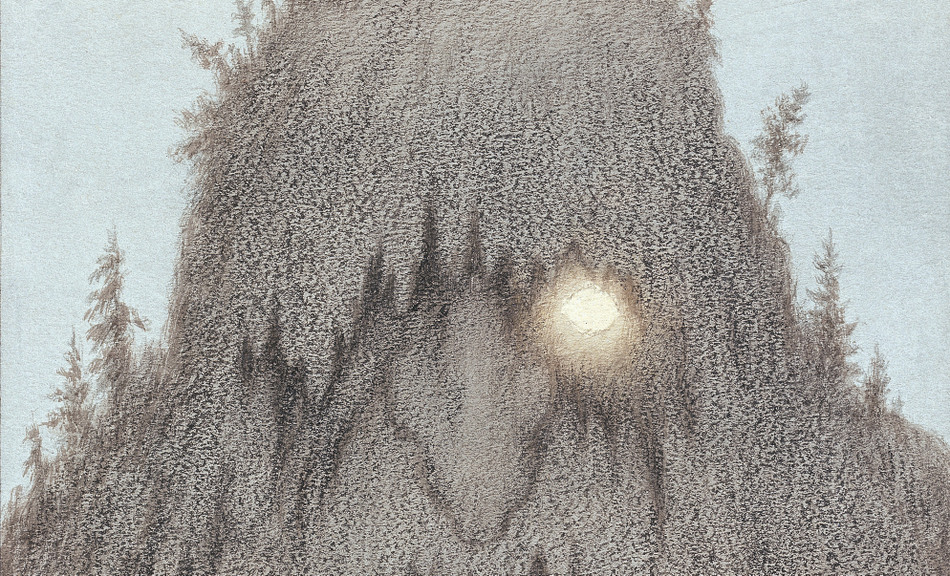

The uncanny, the inexplicable and the incomprehensible have always been topics in the visual arts (see for example Albrecht Dürer’s Knight, Death and Devil, the uncanny fantasies of Hieronymus Bosch, and Johann Heinrich Füssli’s The Nightmare). The famous “Carceri” by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, created between 1745 and 1750, impressed his 18th-century audience with their atmosphere of uncanniness and inaccessibility. Francisco de Goya’s famous etching The Sleep of Reason Brings Forth Monsters (ca. 1799) is a step into new thinking; a hundred years later, Sigmund Freud wrote the epochal work The Interpretation of Dreams. After the masterful series by Goya around 1800, it was primarily the works of the Symbolists in Germany, France, Belgium and Italy that were permeated by uncanny ideas. At the end of this long line of artists stand the figures of Edvard Munch, James Ensor and Alfred Kubin, whose works portrayed their own exaggerated fears and emotional states in artistically consummate form. A painting might not, as for example with Munch, seem so uncanny at first, but one senses subliminally the unsettledness from which it arose. Munch and others had the ability to make the hidden visible.

In his early Expressionist period (1911 and 1912), Egon Schiele created a number of unsettling, mystical paintings such as Revelation, Dead City, The Self Seer and The Hermits, a modern danse macabre.

The exhibition offers an in-depth view into the emotional abysses of artistic imaginations. These “visions of the invisible” transport us into the world of dreams (or nightmares) and ghosts, into the sphere of the occult. The depictions of various fears tell of death, loss and sexuality, or also of “evil.” “Symbols of the subconscious” can be discovered behind masks, at the end and the beginning of stairways, in mirrors and in water surfaces of indeterminate depth. The power of secret, unimaginable stories fascinated the artist in many respects. Another recurring theme is “the uncanny home”: Insecurity, fear and danger break into the seemingly secure and familiar ambience of the home.

The highlights of the exhibition include, alongside works by Edvard Munch (including Angst, Puberty, The Sick Child, Madonna and Self-Portrait in Hell), those of Belgian painter James Ensor, paintings by Arnold Böcklin and Gustave Moreau, and Cuno Amiet's triptych Hope-Caducity, a key work of symbolism.

The various connections to the literature of that period can be seen for example in Ensor’s and Kubin’s reactions to Edgar Allan Poe, or in the illustrations by Felicien Rops for Les Diaboliques by Barbey d’Aureyville. Fascinating are also the works by Fernand Khnoppf and Georges Minne based on Georges Rodenbach’s novel Bruges, the Dead City.

Alongside the Munch Museum in Oslo, which at over 30 objects is the main lender for this exhibition, other prominent lending institutions include the Musée Victor Hugo in Paris, Kunsthaus Zurich, the National Museum in Oslo, the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts, the Museum Kröller-Müller in Otterlo, the Civic Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Arts in Turin, the Städel Museum in Frankfurt and the Von der Heydt Museum in Wuppertal.

The 300-page, completely color-illustrated catalog features contributions by art historians, culture experts and psychologists focusing on various aspects of the theme: they examine the significance of the uncanny in the work of Edvard Munch and James Ensor, as well as the influence which occultism, “magnetism” and “Mesmerism” had on artists of the day. The “tipping” of the idyll into the horrifying or irritating in the works of Max Klinger is also examined, as is the special stylistic device of twilight and its meaning. Finally, the psychology of perception is drawn upon in order to shed light on the reasons why we find something to be irritating or fear-inducing or uncanny. Without question, this exhibition owes its character and importance to the great number of major, large-format works by Edvard Munch that will be presented.

On the other hand, works by James Ensor (which are seldom seen in Vienna), Alfred Kubin, Giovanni Battista Piranesi and other artists will serve to emphasize the general theme and offer a wider view of the limitless human imagination’s artistic offshoots.

But most importantly, things that are mysterious or inexplicable will always evoke curiosity and interest.

Share and follow